I was playing around with GeoGebra and made this applet about one of the simplest, but most intersting dynamical systems: the rigid rotation of a circle. Let me tell you a little about this fascinating subject.

Let denote a circle. For simplicity, let’s think of it as a circle with circumference 1. Let

be any real number. Define a function

as follows: if

is a point on

, then

is obtained by rotating

counterclockwise

units.

There are a few other equivalent ways of thinking of this. You may want to think of as the interval

with the points 0 and 1 glued together. Or you may want to think of it as

; that is, take the real number line and wrap it up like a slinky so that all points that differ by an integer are glued together. In these cases we can write our function as

.

We may view this function as a dynamical system. Given a point , we obtain the orbit of

by plugging it into

repeatedly:

. As usual we will use the familiar notation that

compositions of the function,

, is denoted

. However, in this case

. In other words, rotating

times by

is the same as rotating once by

.

This is not a chaotic dynamical system—far from it. Points do not get mixed up at all, this is a rigid rotation of the circle.

Cool fact #1.

The behavior of the orbits differ depending on whether is or is not rational. If

is rational, then every point is periodic. The period of each point is the same; it is the value of the denominator of

(assuming

is expressed as a reduced fraction). On the other hand, if

is irrational, then not only are the orbits not periodic, they are dense in the circle. By this we mean that the orbit “fills up” the entire circle (or more precisely, given any point of the circle, there is a subsequence of the orbit that converges to this point).

Theorem. If is rational, then every point is periodic. If

is irrational, then every point has a dense orbit.

Cool fact #2.

The previous theorem states that the orbit of any point under an irrational rotation is dense. However we can say more than this. It turns out that if we look at the limiting behavior of an orbit, we see that it fills up the circle uniformly (technically, we say that the function is uniquely ergodic).

Theorem. Let be irrational and

be an arc in

. Let

be the cardinality of

. Then

.

In other words, the fraction of the time that the orbit spends in is precisely the length of the interval

.

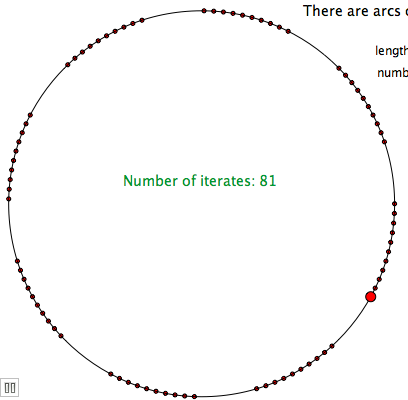

Cool fact #3.

Consider a finite orbit segment: . These

points divide the circle into arcs various lengths. It turns out that for a fixed

, the lengths come in only one, two, or three sizes. Moreover, if there are three lengths, then one is the sum of the other two!

Three Gap Theorem (The Steinhaus Conjecture). The points divide

into arcs of one, two, or three lengths. If there are three lengths, then one is the sum of the other two.

To see the three gap theorem in action, view this GeoGebra applet.

There is a lot more one can say about rigid rotations of the circle; they have interesting connections to dynamical systems, topology, the study of continued fractions, number theory, symbolic dynamics, etc. Go explore!

Cool! I think the fact that is dense can be prove by using Pigeon Hole Principle.

is dense can be prove by using Pigeon Hole Principle.